The Chosin Few

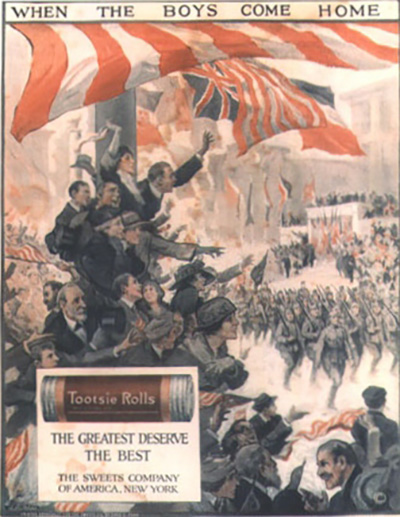

During the Korean War, the First Marine Division met the enemy at Chosin mountain reservoir in subfreezing temperatures. Out of ammunition, Marines called in for 60mm mortar ammo; code name “Tootsie Rolls.” The radio operator did not have the code sheets that would tell him what a “Tootsie Roll” was, but knew the request was urgent; so he called in the order. Soon, pallets of Tootsie Roll candies parachuted from the sky to the First Marine Division! While they were not ammunition, this candy from the sky provided well needed nourishment for the troops. They also learned they could use warmed Tootsie Rolls to plug bullet holes, sealing them as they refroze.

Over two weeks of incessant fighting, the 15,000-man division suffered 3,000 killed in action, 6,000 wounded and thousands of severe frostbite cases. But they accomplished their goal and destroyed several Chinese divisions in the process. Many credited their very survival to Tootsie Rolls. Surviving Marines called themselves “The Chosin Few.”

Recent Comments