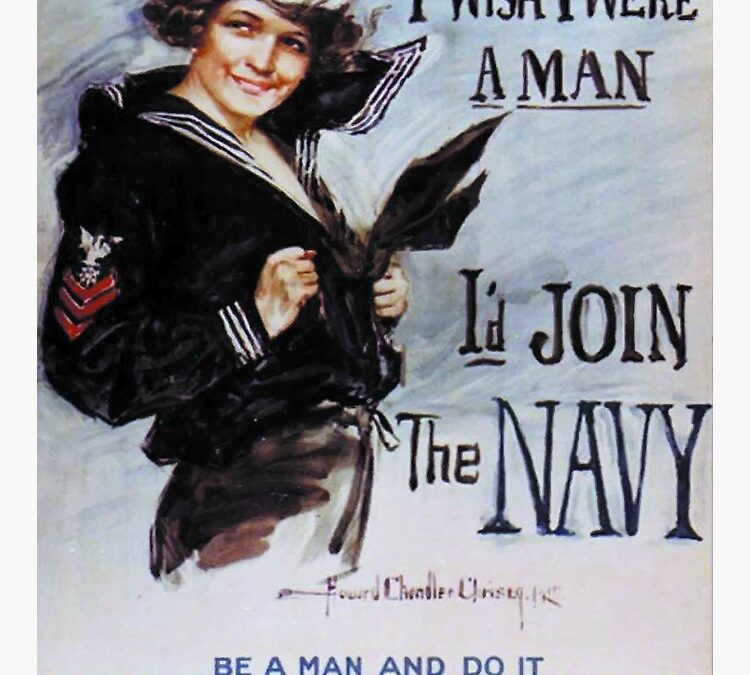

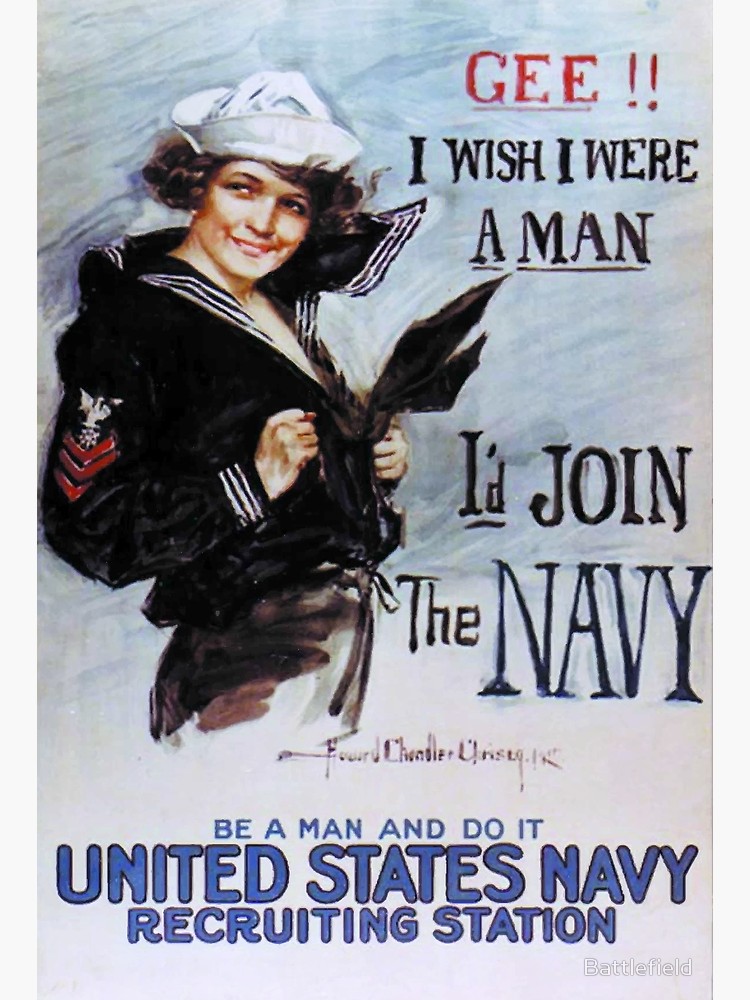

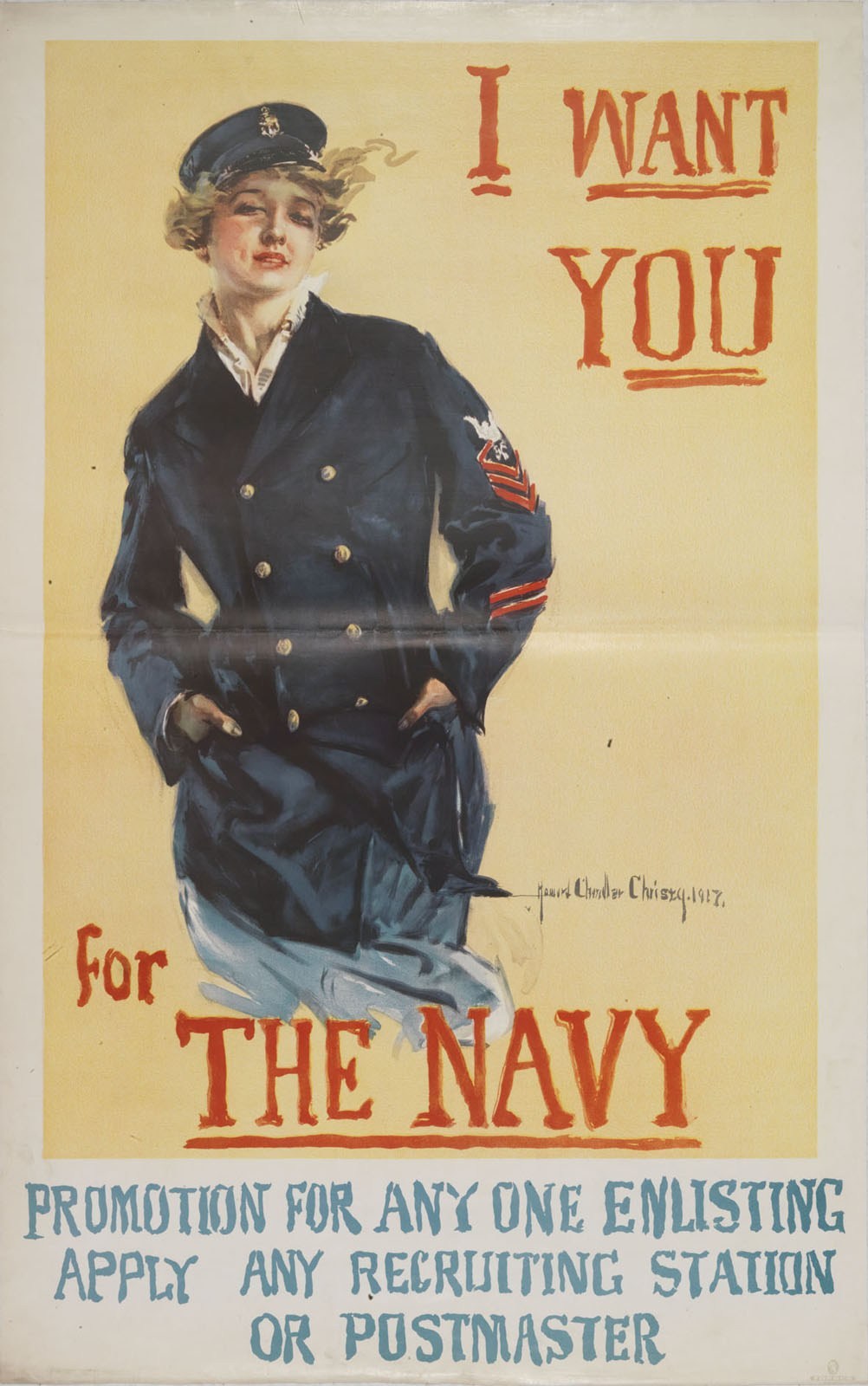

Creel set out to systematically reach every person in the United States multiple times with patriotic information about how the individual could contribute to the war effort. The CPI also worked with the post office to censor seditious counter-propaganda. Creel set up divisions in his new agency to produce and distribute innumerable copies of pamphlets, newspaper releases, magazine advertisements, films, school campaigns, and the speeches of the Four Minute Men. The CPI created colourful posters that appeared in every store window, catching the attention of the passersby for a few seconds.[8] Movie theatres were widely attended, and the CPI trained thousands of volunteer speakers to make patriotic appeals during the four-minute breaks needed to change reels. They also spoke at churches, lodges, fraternal organizations, labour unions, and even logging camps. Creel boasted that in 18 months his 75,000 volunteers delivered over 7.5 million four-minute orations to over 300 million listeners, in a nation of 103 million people. The speakers attended training sessions through local universities and were given pamphlets and speaking tips on a wide variety of topics, such as buying Liberty Bonds, registering for the draft, rationing food, recruiting unskilled workers for munitions jobs, and supporting Red Cross programs. Historians were assigned to write pamphlets and in-depth histories of the causes of the European war.

Recent Comments