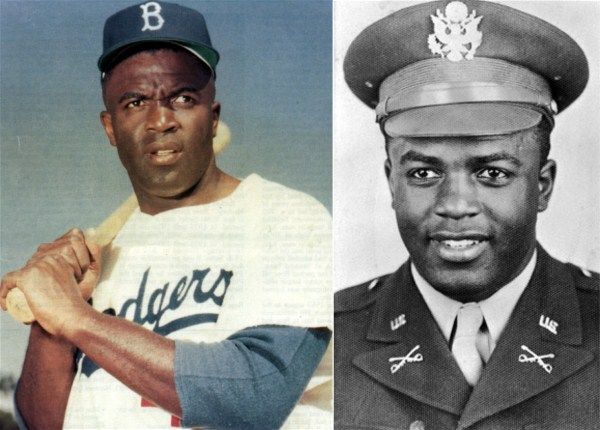

Tuskegee Airmen

The Tuskegee Airmen were a group of African-American and Caribbean born fighter and bomber pilots who fought in WWII. They served in the US Army Air Forces as the 332nd Fighter Group and the 477th Bombardment Group. The Tuskegee Airmen included the pilots, navigators, instructors, and maintenance and support staff who all helped keep the pilots and planes in the air.

In 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced that he would be expanding the civilian pilot training program in the US due to Europe teetering on the verge of war. As the Army Air Corps (AAC) began boosting its training program, civil rights groups began arguing that black Americans should be included instead of segregated from the expansion.

In September 1940, the White House announced that the AAC would begin training black pilots at the Tuskegee Army Airfield in Tuskegee, Alabama. There were 13 members of the first class of aviation cadets in 1941, and ultimately the program would train around 1,000 pilots, along with 14,000 navigators, bombardiers, instructors, mechanics, and other maintenance and support staff.

In 1942, the Tuskegee-trained 99th Pursuit Squadron was deployed to North Africa. They flew their mission in second-hand P-40 planes, which were slower and harder to maneuver than those that the Germans were flying. This led to complaints from their assigned fighter group, and lead to 99th being relocated to Italy to fly alongside the 79th Fighter Group. During this time, pilots from the 99th shot down 12 German fighters in two days, making steps towards proving themselves in combat. The 99th was awarded two Presidential Unit Citations for outstanding tactical air support and aerial combat in the 12th Air Force in Italy.

In February 1944, the 99th was met by the 100th, 301st, and 302nd fighter squadrons to form the new 332nd Fighter Group. After this merge, the pilots of the 332nd began flying P-51 Mustangs to escort heavy bombers during raids into deep enemy territory. The tails of the P-51 Mustangs were painted red for identification, thus earning them the nickname “Red Tails”.

The 332nd was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for its; longest bomber escort mission to Berlin on March 24, 1945, where the Red Tails destroyed three German ME-262 jet fighters, and damaged five additional jet fighters.

The Tuskegee Airmen ran over 200 escort missions, during which time only about 25 bombers were shot down by enemies, giving them one of the lowest loss records of all escort fighter groups, and was impressive compared to the average 46 bombers lost by the 15 Air Force. This put them in constant demand for their services by allied bomber units.

The Tuskegee Airmen had flown more than 15,000 individual sorties during their two years of combat, and destroyed or damaged 36 German planes in the air, and 237 on the ground. They also destroyed nearly 1,000 rail cars, transport vehicles, and a German destroyer.

The 332nd ran its last combat mission in April 26, 1945, two weeks before the German surrender.

The Tuskegee Airmen overcame prejudice to become one of the most highly respected fighter groups of WWII. They ultimately paved the way for the end of segregation in the US military.

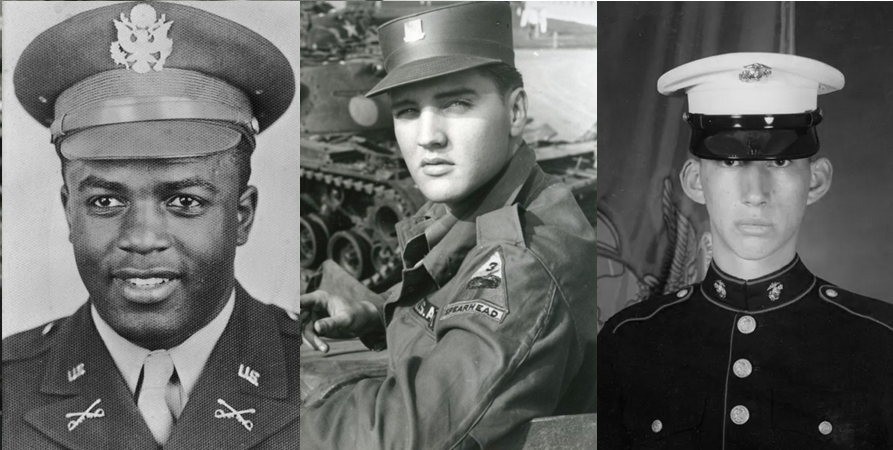

After their return home, one of the 13 original cadets, Benjamin O. Davis Jr, went on the become the first black general in the new US Air Force. Another Tuskegee Airman, George S. “Spanky” Roberts became the first black commander of a racially integrated Air Force unit, and eventually retired as a colonel. And in 1975, Daniel “Chappie” James Jr. went on to become the nation’s first black four-star general.

Another notable Tuskegee Airman was Charles Alfred “Chief” Anderson, who in 1929 earned his pilot’s license, and in 1932 became the first Black American to receive a commercial pilot’s certificate, and subsequently make a transcontinental flight. As chief flight instructor at Tuskegee, he famously flew First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt on an aerial tour, convincing her to encourage her husband to authorize military flight training at Tuskegee.

In 2007, more than 300 of the original Tuskegee Airmen received the Congressional Gold Medal from President George W Bush. Then in 2009, the surviving Tuskegee pilots and support crew were invited to attend the inauguration of the nation’s first black president.

Recent Comments