Medics of WWII

Medics in World War II were the front line of battlefield medicine. In the American army, a battalion of some 400 to 500 men typically would have about thirty medics or aidmen; although sometimes attrition made that number much smaller. Their job was not to conduct extensive treatment of the wounded, but to stabilize them and to prepare them for evacuation to field hospitals or medical centers to the rear. They were trained to stop bleeding, apply dressings, sprinkle sulfa powder on wounds as an antiseptic, and to administer morphine as a sedative. More elaborate medical treatment would wait. Tragically, the medics often had to make the decision of which wounded soldiers were beyond help, and resolutely move on to the next wounded man. Medics from other allied nations, and even Axis nations, performed the same basic functions and displayed comparable courage.

On D-Day, June 6, 1944, dozens of medics went into battle on the beaches of Normandy, usually without a weapon. The large red cross on their helmets was supposed to protect them, and Germans usually (but not universally) respected that convention. But even aside from the threat of direct enemy fire, being a combat medic was a dangerous assignment; shell fire and shrapnel drew no distinction between combatants and noncombatants. On D-Day, and especially on Omaha Beach, evacuation of wounded soldiers was a nearly impossible task. Not only did the number of wounded exceed expectations, but the means to evacuate them did not exist. Landing craft off-loading invasion personnel had no time to carry the wounded back to the fleet, and were not under orders to do so. While some did assist in medical evacuation, most of the wounded on the beaches had to be brought forward to cover, or left where they had fallen. The Normandy Invasion is one of the few battles in history where the wounded were moved forward, into fire, whether than back, away from the fighting.

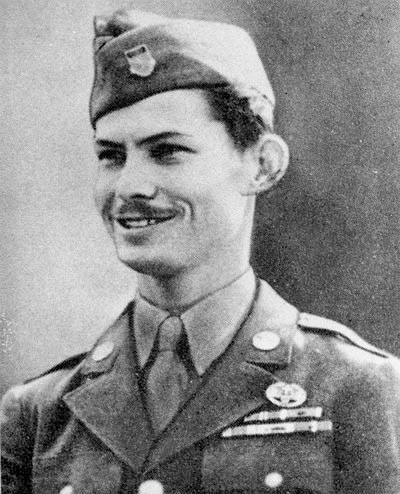

Medics were sometimes chosen for their medical expertise; more often they had to be trained from scratch. Some were conscientious objectors who opposed the taking of life and were assigned this role as an alternative to a combat role. One such medic was PFC Desmond Doss of Lynchburg, VA, who refused to carry arms due to his religious faith, but who wanted to serve his nation in a noncombatant role. On Okinawa in May 1945, Doss single-handedly saved the lives of some 75 men by braving enemy fire to rescue them. He was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the first conscientious objector and one of only eleven medics in WWII to be so honored.

Recent Comments